Hello again, fellow Sloth Investors.

How has this February been for you so far?

Mrs. Sloth and our mini sloths have recently returned from a Lunar New Year trip to Thailand. Interestingly, although we’ve lived in Hong Kong for six years, it’s our first overseas trip during that particular holiday season (Covid 19 has much explaining to do!).

In addition to the hospitality of the Thai people and the consistently pleasant weather, a key reason why I love visiting Thailand is because of the cuisine. Thai food is rich, not only in taste but in colour. You’ll typically find ingredients such as lemongrass, ginger, garlic, chillies, coconut, tamarind, and lime leaf, to name but several. Thai food definitely appeals to my taste palate.

A Personal Finance Palate

As many of you will know, the term ‘palate’ refers to our taste or liking for something. Commonly, the word connects to food.

For instance, if you’re at a restaurant with family or friends, your selections from the menu will be dictated by your unique taste palate.

Just as each person possesses a unique taste palate, with specific likes and dislikes about food, each of us has our own personal finance palate, i.e., the distinctive, individual choices about how we spend, save, and invest our money.

Many factors can affect our personal finance palate. These include, but are not limited to, our age, our family background, and our previous experiences.

The Difference Between What We Say and What We Do

There can often be a startling difference between what we recommend others do with their money and what we actually do. For example, according to Morningstar, around 50% of US mutual fund portfolio managers do not invest a cent of their own money in their funds1 .

Similarly, this type of decision making doesn’t just occur within the realm of finance. It also takes place within the field of medicine.

In 2011, Ken Murray, a professor of medicine at USC (University of Southern California), wrote an essay that elaborated upon the degree to which doctors selected different end-of-life treatments for themselves than they recommended for their patients2.

Murray writes:

“What’s unusual about them (doctors) is not how much treatment they get compared to most Americans, but how little. For all the time they spend fending off the deaths of others, they tend to be fairly serene when faced with death themselves. They know exactly what is going to happen, they know the choices, and they generally have access to any sort of medical care they could want. But they go gently.”

The difference between what someone advises you to do and what they do for themselves could lead to overthinking or even to charges of hypocrisy.

However, if anything, it accentuates the point that when dealing with complex, emotional issues that affect you and your family, there is no definitive, singular answer.

The management of your personal finances is much the same.

What Affects the Decisions You Take With Your Money?

It can be fascinating to learn more about the unique decisions that others take with their money.

Here’s Morgan Housel, author of the book ‘The Psychology of Money’, on his propensity for keeping a large percentage of his assets in cash:

“We also keep a higher percentage of our assets in cash than most financial advisors would recommend - something around 20% of our assets outside the value of our house. This is also close to indefensible on paper, and I’m not recommending it to others. It’s just what works for us. We do it because cash is the oxygen of independence, and - more importantly - we never want to be forced to sell the stocks we own. We want the probability of facing a huge expense and needing to liquidate stocks to cover it to be as close to zero as possible. Perhaps we just have a lower risk tolerance than others. But everything I’ve learned about personal finance tells me that everyone - without exception - will eventually face a huge expense they did not expect - and they don’t plan for these expenses specifically because they did not expect them….I’m saving for a world where curveballs are more common than we expect.” 3

Family Finances

Our family can play a decisive role in our decisions about money and, ultimately, our personal finance palate.

Ingroup bias refers to the tendency for individuals to favourably treat members of their own group compared to other groups. How does this specific bias relate to investing? Let me explain with an example from my own life.

As a young man, my view of the stock market was framed by two leading influences, the media, and my family.

On those occasions when the stock market was mentioned on television or in newspapers, it was invariably because of volatility or a sharp decline. Unfortunately for me, as an 18-year old, I was yet to learn about the media’s bias towards negativity.

In addition to this, coming from a family that never invested, and that warned me off the supposed dangers of investing, my mind was quickly, although wrongly, made up. I was quick to decide that the stock market was definitely not for me, no one in my family had ever invested and so I falsely concluded that it couldn’t be the right course of action to take with my money. For too many years, the notion of investing never entered my personal finance equation. It simply wasn’t a part of my financial palate.

Little did I know how wrong I was.

A key reason then, which explains my premature, naive decision to never invest, was the influence of my family.

Their negative view of the stock market affected my own view, meaning that I had allowed ingroup bias to influence my perception of investing.

Whether it relates to investing or not, I urge you to consider whether you have ever allowed the groups that you are a part of to act as an echo chamber, thereby potentially causing you to take the wrong course of action.

Take some time to reflect on these questions.

What do you do when you are confronted with a course of action or a perspective that conflicts with your pre-existing views?

Do you possess the humility to critique your prior perspective or, do you take a mental shortcut and simply refuse to consider whether there may be some validity to an alternative viewpoint or course of action?

In summary, a key reason why it took me so long to even consider investing is that I didn’t want to confront the pre-existing views that defined my view of the stock market, i.e. I considered it to be too risky, not for everyday people like me and something best left to the ‘professionals’.

The influence of my family played a key role.

I had yet to read, discuss and learn more about investing. Once I had learned a great deal more about investing, this then led to the construction of the 5 bedrock principles of the Sloth Investor.

Here’s what Brian Portnoy, author of ‘The Geometry of Wealth’, has to say about his parents and money growing up:

“My parents fought about money all the time. It’s not that we were lacking. My dad made good money and my mum was good at spending it. They didn’t seem to like each other for many reasons, and money served as both a language of conflict and a currency of control. Following the divorce, issues of alimony and child support extended the unpleasantries for decades. Fast forward to recent times, I’m sometimes asked what I learned from my parents about money. The short answer is always: Nothing. A longer, harsher answer is that money is a tool: to buy things and to hurt others.” 4

Stepping aside from his childhood, here is what Portnoy has to say about the money decisions taken by him and his wife:

“In the context of high earnings, Tracy (my wife) and I have been disciplined in our spending, not because of a rigorous budget, but because we just don’t covet the big ticket items (cars, jewellery, wine, art, fancy travel) that seem to seduce others. Thus, the bedrock of our financial health has been our disposition to save and, by the same token, an aversion to debt. We paid off our mortgage a while ago. I know the ‘spread’ on what I might have earned with that cash. I don’t care. I love not having a mortgage, and no other debt to speak of.” 5

It was interesting to read what Brian Portnoy had to say about the money decisions he and his wife have taken.

Stepping aside from matrimony, what does the research tell us about money and dating? Well, if saving money is a cornerstone of your financial palate this will beneficial for those of you currently on the dating scene.

Jenny G. Olson, an assistant professor of marketing at Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business, and Scott I. Rick, an associate professor of Marketing at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business, explored the dating scene to discover if singles preferred big spenders or people who were responsible with their money6. Overwhelmingly, Olson and Rick’s study showed that the participants favoured savers.

Here’s a final point now on family and money from none other than comedian, writer and director Ricky Gervais. This is a recent social media post by him:

‘I was taught that ability was a poor man’s wealth - I LOVE that Ricky!

An ‘Investing Palate’

I've spent some time citing others' thoughts on spending, saving, and mortgages, but what about investing?

Commonly, the acronym ‘IP’ is shorthand for ‘intellectual property’ or ‘internet protocol’.

However, I’m now going to use ‘IP’ to refer to ‘investment palate’ – i.e. the specific way that an individual chooses to invest.

I’m sure many of my readers will be keen to learn how significant figures within the domain of finance invest their money. What does their IP, or ‘investment palate’ look like?

These are the thoughts of the aforementioned Morgan Housel, author of the book ‘The Psychology of Money’:

“If I had to summarise my views on investing, it’s this: Every investor should pick a strategy that has the highest odds of successfully meeting their goals. And I think for most investors, dollar-cost averaging into a low-cost index fund will provide the highest odds of long-term success. That doesn’t mean index investing will always work. It doesn’t mean it’s for everyone. And it doesn’t mean active stock picking is doomed to fail. In general, this industry has become too entrenched on one side or the other - particularly those vehemently against active investing…life is about playing the odds and we all think about the odds a little differently. Over the years I came around to the view that we’ll have a high chance of meeting all our family’s financial goals if we consistently invest money into a low-cost index fund for decades on end, leaving the money alone to compound. A lot of this view comes from our lifestyle of frugal spending. If you can meet all your goals without having to take the added risk that comes from trying to outperform the market, then what’s the point of even trying? I can afford to not be the greatest investor in the world, but I can’t afford to be a bad one. When I think of it that way, the choice to buy the index and hold on is a no-brainer for us…we invest money from every pay check into these index funds - a combination of US and international stocks…and that’s about it. Effectively all of our net worth is a house, a checking account, and some Vanguard index funds.”7

Housel is not alone in his advocacy for index funds. This is what Ashby Daniels, a financial advisor with Shorebridge Wealth Management, has to say about them:

“I believe being willing to stick to a diversified portfolio of index funds is the closest thing to an investing superpower that exists in the age of shiny object syndrome. Patience seems to be a much simpler and more satisfying road to our financial goals than always trying to find the next best thing.”8

Let’s now hear one more time from Brian Portnoy, the author of ‘The Geometry of Wealth’. This is how he invests:

“Most of our college and retirement assets are in the Vanguard Total World Stock ETF (VT). At 9 basis point per year (almost free), VT delivers globally diversified equity exposure. If the global stock market does well, we’ll do well. I have zero interest in actively tilting my portfolio by region or sector or other factors. It’s worse than a coin flip’s chance I’d get any of that right. I know lots of very rich fund managers who do this for a living and tend to get it wrong. I’d rather read a book.”9

The Power of Simplicity

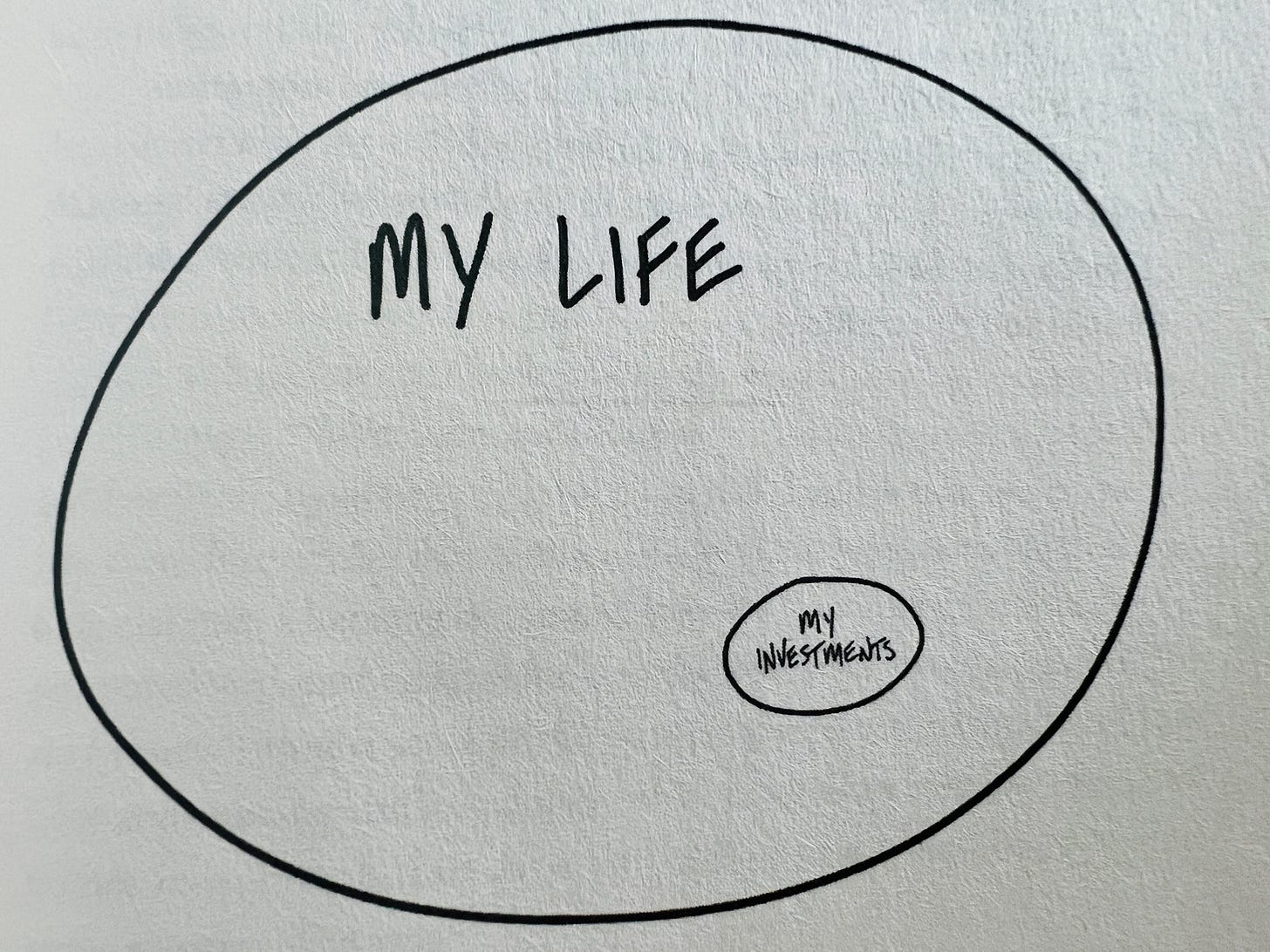

I’ll bring this article to a close now by sharing with you one of my favourite visuals about investing.

The reason is that when I speak to most people about investing, it’s clearly the case that they see it as a means to an end rather than something that they have a deep, unrelenting passion for.

After all, most people have extremely busy lives, whether it be family, friends, or leisure interests, so this naturally means that a significantly large % of people want to keep their approach to investing simple.

Indeed, this explains why the 1st bedrock principle of the Sloth Investor is simplicity.

At this point you may well be wondering about the video content from the Sloth Investor YouTube channel. I’ve previously stated that for my Substack post at the final weekend of the month I will share content from my YouTube channel.

Therefore, what I leave with you now is a discussion between Jay (my podcast co-host) and myself in which I elaborate upon each of the 5 bedrock principles that you see above.

The video will hopefully provide you with a solid understanding of my investment palate.

So long for now!

The Sloth Investor

A. Ram, Financial Times, September 18, 2016.

K. Murray, Zocalo Public Square, November 30, 2011.

Portnoy, B., & Brown, J. (2020). How I invest my money: Finance experts reveal how they save, spend, and invest. Harriman House Limited.

ibid

ibid

Olson, Jenny and Rick, Scott, A Penny Saved Is a Partner Earned: The Romantic Appeal of Savers (September 1, 2017). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2281344 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2281344

Portnoy, B., & Brown, J. (2020). How I invest my money: Finance experts reveal how they save, spend, and invest. Harriman House Limited.

ibid

ibid