Hello again, fellow Sloth Investors.

Firstly, please accept my apologies for the absence of my writing during the month of March. It was an unintended hiatus primarily caused by it being an extremely busy month, particularly in relation to a series of deadlines that cropped up concerning the release of my book ‘The Sloth Investor’ on June 28th.

Take a Look in the Mirror!

The individual investor doesn’t need to look far to encounter what is likely to be the biggest obstacle to their success as an investor. Yes, quite simply, take a look in the mirror and you’ll find it.

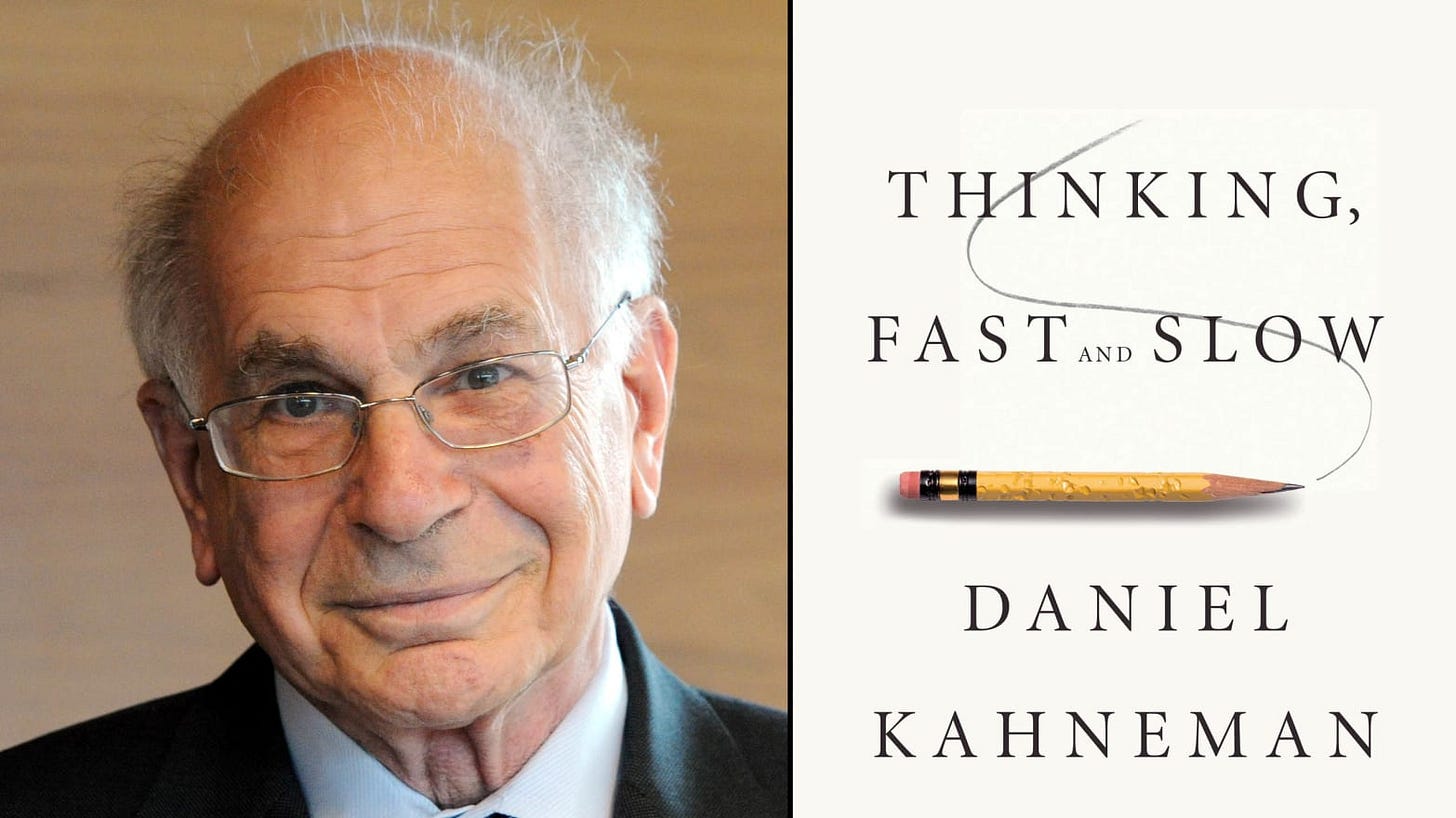

A little under three weeks ago Daniel Kahneman, the pioneer of behavioural economics, passed away.

The award in 2002 of the the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences to Kahneman - not an economist but a behavioural psychologist - was a pivotal turning point in personal finance.

It provided official acknowledgement that improving investor outcomes is as much about managing their behaviour as investing their money in an evidence-based way. Kahneman perhaps understood this better than anyone.

If you’re looking to understand your brain then Kahneman’s 2002 book Thinking, Fast and Slow provides a great starting point.

Humans are undeniably primal creatures. We are not sovereign beings who act with impeccable rationality; we are shaped by primal desires. This is something that Kahneman recognised.

Behavioural economics, the branch of the social sciences that he pioneered, is dedicated to exploring the irrationality of humans when tasked with making individual choices.

One of the finest tributes to the profound impact and legacy of Kahneman’s work comes from David Brooks, a New York Times Opinion columnist. Brooks described Kahneman and his long-time collaborator Amos Tversky as ‘the Lewis and Clark of the Mind’1. This is of course a reference to the American duo who explored much of America’s interior under the supervision of Thomas Jefferson, the president at that time.

Given the expansive scope of Kahneman’s work, and it’s resonance to the field of investing, I have decided to dedicate both this month’s and next month’s personal finance blog post to the domain of investor psychology.

Loss Aversion

A major concept that Daniel Kahneman wrote about was loss aversion.

Are you a sports fan? Do you support a football team, a rugby team, an ice hockey team, or some other sporting team? If you do, then undoubtedly you would have experienced how terrible it feels when your team loses. Doesn’t the feeling of loss always seem to hurt more than the amazing feeling you get when your team wins?

Naturally, as a fan of Tottenham Hotspur football club, I have experienced the pain of loss on many occasions. On the day that I’m composing this article, the pain of loss is particularly stinging (two words…Newcastle United).

It’s difficult to forget about those losses. Curiously, it appears far easier to recall the heartbreak than the successes. Quite simply, we feel the loss of things twice as intensely as we feel the gain.

Loss aversion can be defined as the fear of bad things occurring and it has played a key role in the evolution of the human species. According to McDermott, Fowler and Smirnov (2008)2, the potential for food to become scarce was fatal and so a temperament towards avoiding loss is what caused our ancient ancestors to gather their belongings and hunt and scavenge in a new spot.

Moreover, significant studies have demonstrated that humans care a great deal more about avoiding loss than we do about attaining gain. Writing in the Scientific American3, Dr Russell Poldrack and his team discovered that:

“The brain regions that process value and reward may be silenced more when we evaluate a potential loss than they are activated when we assess a similar-sized gain.”

The researchers found that the reactions in their subjects’ brains were stronger when responding to possible losses than to gains. The researchers labelled this ‘neural loss aversion’. Numerous studies have shown that humans regret losses around two and half times more than gains make us feel good4.

The connections that we can make between loss aversion and investing are clear. During a sustained period of market volatility or, perhaps even a bear market, some investors choose to sell their stock positions as the market starts to dip, thereby locking in losses rather than avoiding them altogether by staying the course.

In such a scenario, in which loss aversion compels investors to revert to cash, we can plainly see evidence of market timing. This is because these very same investors will likely want to re-enter the market when ‘things start to look better’. However, how can these investors know precisely the right time to re-enter? The short answer? They don’t. No one possesses a crystal ball. Moreover, while these investors sit on the side-lines, there’s a strong possibility that they would have missed out on many of the big gains that occur when the market begins to make its inevitable turn upwards.

For some individuals, the fear of loss looms large and they may choose to never invest at all. While such people may deem this choice as a form of security, this security comes with a significantly high cost. The irony is that although they may deem their actions to be of sound judgement, decisions such as this are unsound, once the effects of inflation are taken into consideration. The decision to allow your cash to stagnate, to not utilise it in the stock market, will inevitably, due to the effects of inflation, lead to an erosion of your purchasing power.

How Can Individual Investors Counter the Effects of Loss Aversion?

In a recent conversation with a young staff member of the publishing company that will publish my book I engaged in a discussion about investing (how could I not?).

It was encouraging for me to learn that this individual had started to invest several years ago but this person conceded that they had a tendency to check the value of their portfolio on a daily basis. Given the frictionless way that we can now invest (which is certainly good in some ways) this is perhaps not surprising.

This is what Daniel Kahneman has to say about the ever-increasing tendency for contemporary investors to behave in this way5:

“Closely following daily fluctuations is a losing proposition, because the pain of the frequent small losses exceeds the pleasure of the equally frequent small gains. Once a quarter is enough, and may be more than enough for individual investors. In addition to improving the emotional quality of life, the deliberate avoidance of exposure to short-term outcomes improves the quality of both decisions and outcomes. The typical short-term reaction to bad news is increased loss aversion…you are also less prone to useless churning of your portfolio if you don’t know how every stock in it is doing every day (or every week or even every month). A commitment not to change one’s position for several periods (the equivalent of ‘locking in’ an investment) improves financial performance.”

The above words by Kahneman once again re-iterate the significance of an inactive approach to investing.

Indeed, regular listeners of the Sloth Investor Podcast will know that I consistently begin each episode by staunchly declaring that the sloth is ‘the best animal to characterise successful investing’. As many of you will recognise, a key reason for this is the inactive nature of this creature.

Okay, so as I bring part 1 of ‘Mirror, Mirror on the Wall’ to a close, let’s now examine another cognitive bias.

Information Bias

A key factor that will determine your success as an investor will be your ability to decide which information should be deemed relevant to you making an informed investment decision. Moreover, ignoring irrelevant information will enable you to form a positive path for yourself.

There are innumerable ways that you could allow irrelevant investing information to shape your decision-making process. For instance, you have to remember that much of the investing information that you read online is designed to generate clicks, thereby resulting in additional revenue for the publisher of the content. In addition, the writers of this content are human, like you, and are therefore vulnerable to the very same cognitive biases that may afflict you.

Research has demonstrated that investors who are able to avoid information bias are able to make better investment decisions. For example, a study by Brad M. Barber and Terrance Odean found that individual investors who paid less attention to stock market news achieved better returns than those who paid more attention to the news.6

In January I wrote about the folly of placing too much stock on financial forecasts. Nevertheless, a key reason why individual investors seek out stock market forecasts and watch financial news channels (and will continue to do so in the future) is because of our inherent desire for certainty. A fundamental flaw of human beings is our failure to handle uncertainty effectively. In his book ‘The Daily Laws’ author Robert Greene writes7:

“The need for certainty is the greatest disease the mind faces.”

Fear-inducing articles – or, what I call, ‘Triple I’ articles (irrelevant investing information) – are designed to cause a conflict between your prefrontal cortex and your reptilian brain. When you begin to read articles in the financial media, particularly those that are sensationalist in tone, the temptation is for the impulses of your reptilian brain to take over. However, you must ensure that you allow your prefrontal cortex to quash the impulses of your reptilian brain. So, in conclusion, a sloth investor adds another ‘I’ to ‘Triple I’ by simply ‘ignoring irrelevant investing information’.

That brings to a close part 1 of ‘Mirror, Mirror on the Wall’, an exploration into investor psychology. In four weeks time you’ll be able to read part two.

In two weeks time I’ll be sharing an article that specifically relates to content from the Sloth Investor YouTube channel.

So long for now!

The Sloth Investor

‘On the Evolutionary Origin of Prospect Theory Preferences’ by Rose McDermott, James H. Fowler and Oleg Smirnov. Published in The Journal of Politics, April 2008.

‘What is Loss Aversion?’ by Russell Poldrack. Published by Scientific American in July 2016 – [scientificamerican.com/article/what-is-loss-aversion]

Kahneman, Daniel, Thinking, Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002)

ibid

Brad M. Barber and Terrance Odean, via University of California, Berkeley, Haas School of Business. “All That Glitters: The Effect of Attention and News on the Buying Behavior of Individual and Institutional Investors”, The Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2, 2006, Pages 812–814 (Pages 28–30 of PDF).

Greene, R. (2023). The daily laws: 366 Meditations on Power, Seduction, Mastery, Strategy, and Human Nature. Penguin.